Remember

We also record and publish stories of Arizona’s Holocaust survivors and their descendants.

Yom HaShoah 2024

Yom HaShoah/Holocaust Remembrance

PHA hosts the largest community-wide Holocaust Remembrance Day event in all of Arizona. Yom HaShoah is recognized each year in April or May, coinciding with the 27th Day of Nisan (on the Hebrew calendar) marking the beginning of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising of 1943, when Jewish resistance fighters defied the Nazis and fought for freedom and dignity.

Our annual Yom HaShoah Commemoration includes a procession of local survivors, a candle lighting ceremony to remember the six million Jews murdered in the Holocaust, a keynote address by a local speaker, a survivor’s remarks, an invocation and message from a local rabbi, music, prayers, and the presenting of PHA’s Annual Shofar Zachor Award for outstanding contributions to Holocaust and genocide education. To see photos from our past Yom HaShoah programs please visit our Gallery page https://phxha.com/gallery/

Yom HaShoah Book of Remembrance

As part of our Yom HaShoah Commemoration we pay tribute to those family members who perished in the Shoah and honor those who survived in a Book of Remembrance. Click the button below to download the 2024 Book of Remembrance.

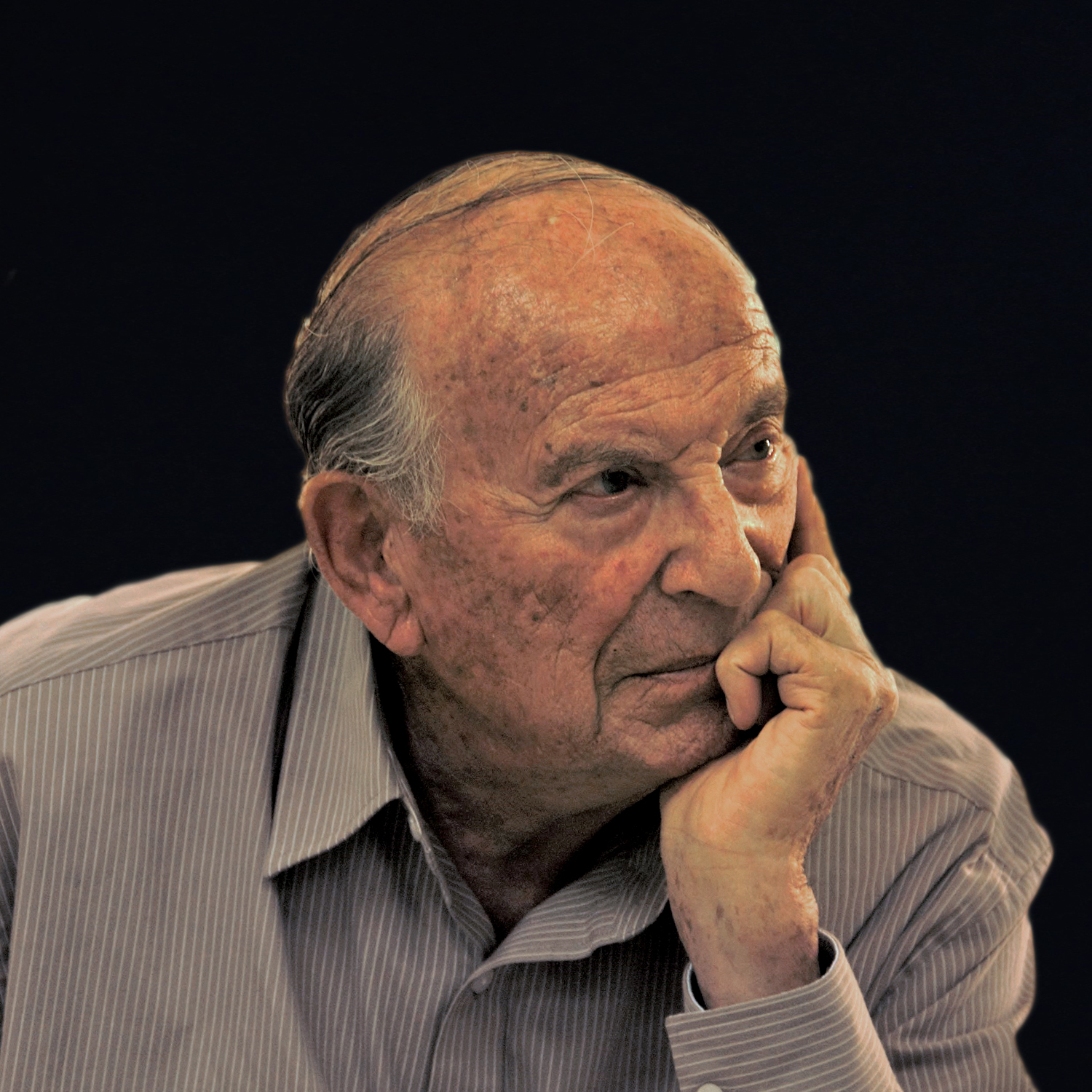

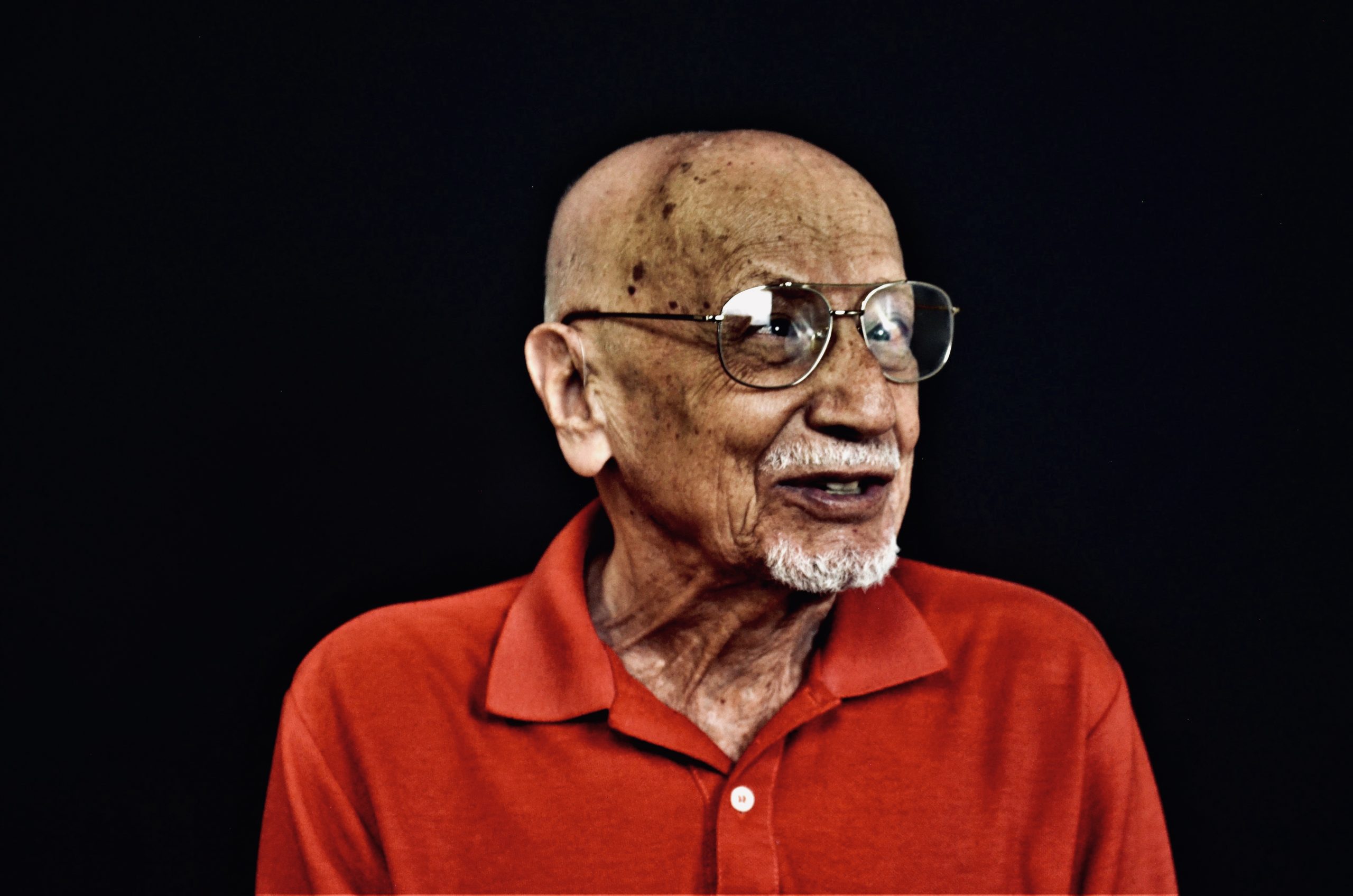

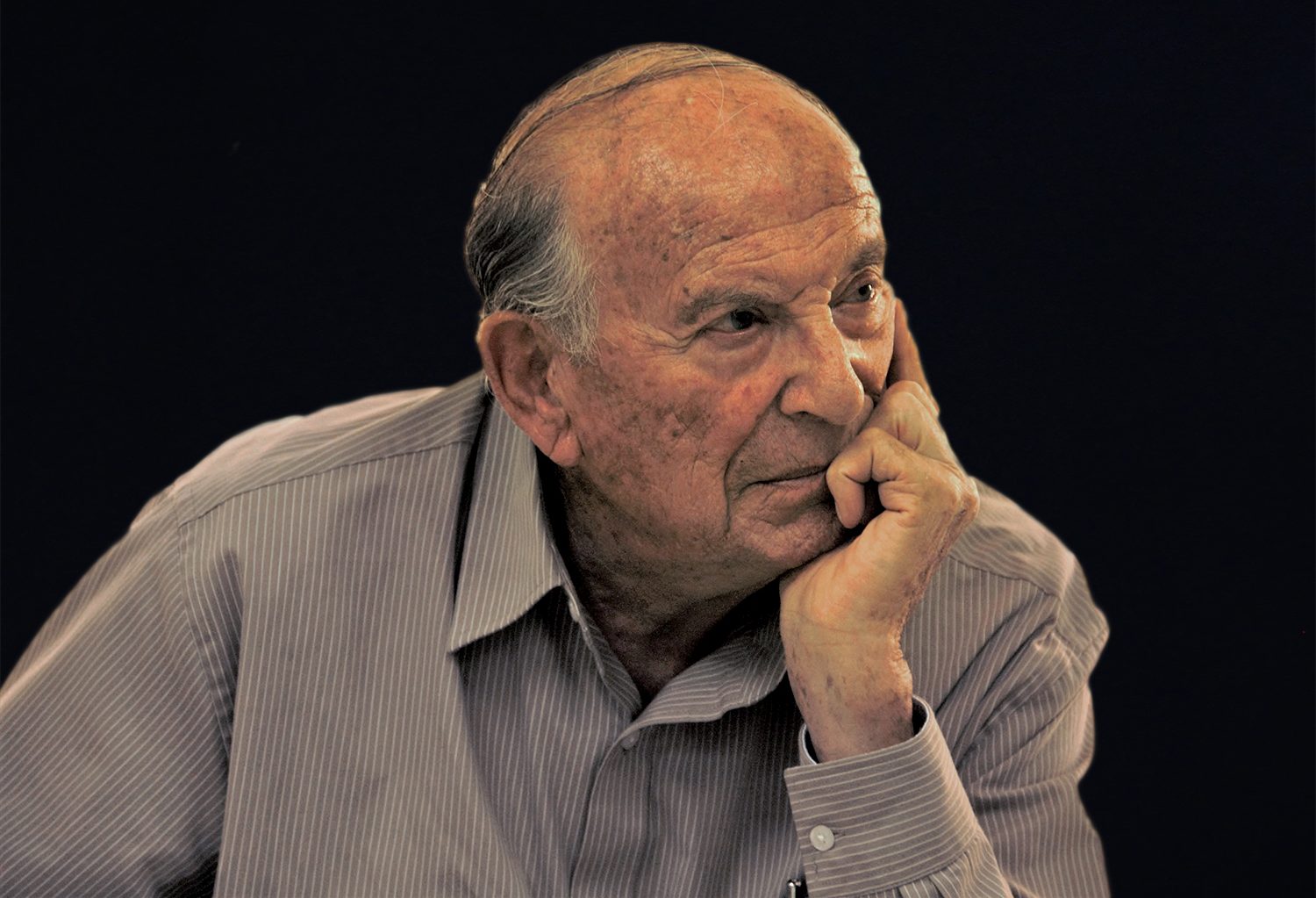

Survivor Stories

The Holocaust was a profoundly tragic time in world history that resulted in the murder of six million Jews, of which an estimated 1.5 million were children. Another five million human beings were also killed, including Roma-Sinti people (“Gypsies”), political dissidents, communists, intellectuals, Jehovah Witnesses, homosexuals, Poles, and people with mental and physical disabilities.

Most Holocaust survivors alive today are over the age of 80. Local survivors’ stories cover a wide range of backgrounds and Holocaust experiences.